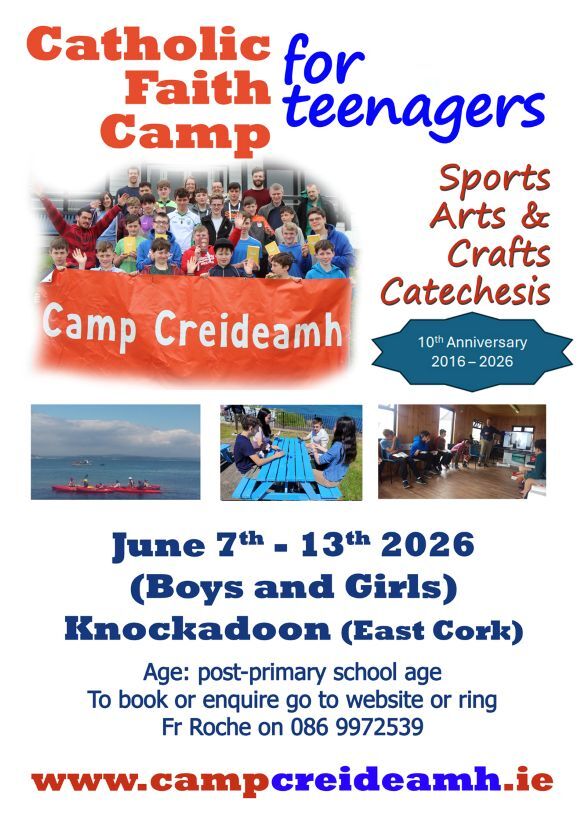

Activities will include catechesis, prayer, sports, hillwalking, kayaking, swimming, music, arts and crafts and other activities.

For bookings go to the website Camp Creideamh

For more information please call Fr. Eamon Roche on 086 9972539

Camp Creideamh - Knockadoon

Camp Creideamh - Knockadoon

The Annual Lourdes Mass - Friday 13th February 2026

Church of the Immaculate Conception, Kanturk, P51 TY36 at 7.30pm

Bishop William Crean will be the Chief Celebrant of the Mass

Cloyne Diocesan Pilgrimage to Knock - Sunday 10th May 2026

Parishes to make their own travel arrangements

Cloyne Diocesan Pilgrimage to Lourdes 29th May – 3rd June 2026

All bookings for the Cloyne Diocesan Pilgrimage to Lourdes should be made through Joe Walsh Tours by telephone 01-2410800, online at Joe Walsh Tours or by post to 89 Harcourt Street, Dublin 2, D02WY88. No booking is definite until a non-refundable deposit payment of €350 per person (plus insurance premium where applicable) has been receipted by Joe Walsh Tours. Early booking advisable.

Pilgrims who would like to travel with the Special Assisted Section should apply to: Cloyne Diocesan Pilgrimage to Lourdes, c/o Parish Secretary, 27/28 Bank Place, Mallow, Co. Cork. Tel: 022-20276. This special assisted/sick section is accommodated at the Accueil Notre Dame. Acceptance for travel with the special section for the sick is subject to approval of the Pilgrimage Medical Board. The closing date for receipt of application is 31 March 2026.

Cloyne Diocesan Pilgrimage to Lourdes 29th May - 3rd June 2026

Cloyne Diocesan Pilgrimage to Lourdes 29th May - 3rd June 2026

on pastoral planning for the future

My dear people,

To live is to change, is a pearl of wisdom from St. John Henry Newman, a convert to the Catholic faith in the 19th Century. To live in the 21st Century is an experience of constant change, social, cultural and technological. Viewing “Reeling in the Years,” the television series depicting life in former times is a dramatic reminder of the extent of the change we have experienced.

The Church whose life and presence within our communities and parish has had to adjust to and

manage the change taking place in society. One particular pattern has been evident for some years

now is the decline both in profession of Christian faith and its practice through the attendance at Holy Mass,

which, for the believer, is an obligation in faith. The consequence of this generational shift from family and

parish community attendance has seen a similar decline in responding to the call to Priesthood and Religious life. Despite this pattern in the Diocese of Cloyne, in all the parishes there are faithful practicing prayer congregations who witness to and support one another in faith.